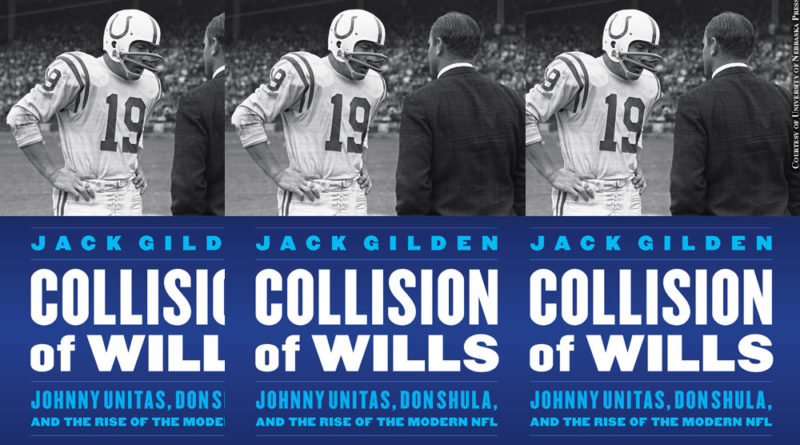

Excerpted from “Collision of Wills: Johnny Unitas, Don Shula, and the Rise of the Modern NFL” by Jack Gilden by permission of the University of Nebraska Press. Copyright 2018 by Jack Gilden.

From Chapter Five The Colts’ Greatest Season Yet

Vince Lombardi himself seemed to hold just one team in high esteem, and that was the Baltimore Colts under Weeb Ewbank. Despite some painful losses to Baltimore, he was generous in his praise of Johnny Unitas. After a 1959 Colts victory over the Packers, Vince told reporters that Johnny U was “the best quarterback I’ve ever seen.” In 1960, when Lombardi finally beat the Colts for the first time as a head coach, he called it “my greatest day in football.” In 1961, in the midst of his first championship season, he told reporters that Unitas was “the greatest football player in the world.”

Unitas was unimpressed with all the praise. “That and a dime will get you a cup of coffee,” he said.

Despite Lombardi’s ardor, the Packers bid adieu to Weeb by beating Baltimore twice in ‘62. In 1963 they rudely welcomed Don Shula and swept him, too.

In 1964 everything seemed to point to more of the same between Green Bay and Baltimore. But when the Colts’ plane touched down in Wisconsin for an early-season matchup, nothing went as others thought. And in the tiny statistics a fascinating story was told.

Shula’s team was finding the winning balance. Unitas threw the ball just twelve times against the Packers, while Colts runners carried thirty-seven times and gained 123 yards. All of a sudden Green Bay’s swarming pass rushers couldn’t pin their ears back for Johnny U and disrupt his rhythms anymore. They had to hesitate and consider that there was something else that might afflict them. With that tiny advantage Unitas was sacked only once on the day, for 9 yards. Meanwhile, he slung it down-field for 154. He connected with his old target Lenny Moore in the first half for a 52-yard touchdown. According to The Baltimore Sun, Moore was “yards and yards behind the defender,” who was necessarily drawn in to protect against the effective running game. While the suddenly balanced offense was making its mayhem, those old marauders — Gino Marchetti, Bill Pellington, and their henchmen — swallowed Bart Starr whole. The Colts sacked him six times, good for 47 yards of lost ground. Meanwhile, when he could actually stay upright long enough to pass, the results were no better. The Colts’ defenders intercepted Starr three times.

Despite it all, though, Green Bay was in their usual position to win the game at the end. The Pack needed only two points to pull it off when they found themselves in easy field goal range with time ticking off the clock. But Starr inexplicably attempted to pass, and the ball ended up in the hands of Baltimore’s Don Shinnick. That, and a missed extra point by Paul Hornung earlier in the game, ensured the Colts’ 21–20 victory.

The breaks that typically went Green Bay’s way were, for once, in Baltimore’s favor. More than that, the Colts had their old balance back. It seemed that Baltimore could run and pass as well as play incredibly rough defense.

In week three those indicators would all prove true beyond everyone’s imagination when they met another old rival with a legendary coach.

The defending-champion Bears and George Halas came to Baltimore.

The Colts had a long, stormy history with Halas and his Chicago grizzlies. Every game against Papa Bear was a brutal struggle. A Colts victory at Wrigley Field in 1960 bolstered the Unitas legend even while it dashed all hopes for a third straight title under Ewbank. The Colts left Chicago that day leading the West by two games with just four to go. But with seventeen seconds left on the clock, the Bears held a 20-17 lead. Unitas had already been sacked five times on the day. The last of them was a vicious hit by Doug Atkins that split the bridge of Unitas’s nose. Blood was spurting out of the wound and both nostrils. The referee, surveying the gruesome scene, told the quarterback to leave the field. As the legend has it, Johnny U instead ejected the official from his huddle and cauterized the bleeding with mud scooped from the Wrigley turf and shoved into his two nostrils by his teammate Alex Sandusky. Jim Parker later recalled that the sight of the wound and its filthy remedy almost set him to vomiting right on the field. But the patient himself played on as if nothing had happened. Unitas dialed Lenny’s number, and with the mud and the blood streaming down his face he hit the Reading Rocket with a perfectly thrown 37-yard pass in the corner of the end zone. Lenny hauled in the missile, and the referee threw his arms in the air in two parallel lines just as time expired. When asked to explain how it was possible, Unitas missed the point of the question entirely. “I thought Lenny could beat [the corner- back] on that pattern,” he obtusely said.

Unitas bore the scar from that Bear wound on the bridge of his nose for the rest of his life.

Dramatic as that conquest of Halas may have been, it was nothing more than a pyrrhic victory. The game was so brutal, and extracted such an awful physical toll on the Colts, the team lost all four of its remaining games. After the season ended (with a loss to San Francisco), Weeb’s thoughts were still in Chicago. “We won the game but lost the title there,” he said in pity for himself and his hapless and drained men.

Now, in 1964, facing off against the Bears would be unlike any of the previous brutal Chicago experiences. This time the Colts embarrassed and humiliated the Bears, 52–0. It was the worst whipping in the entire history of the old and venerable Chicago franchise. Just as they had against the Packers, the Colts’ runners really poured it on. They lugged the ball forty-one times and scampered for 213 yards against the Monsters of the Midway. Unitas threw only thirteen passes, but those were good enough for 247 yards and three touchdowns.

The rest of the season went much the same way. The running attack enabled the passing attack, and the passing attack featured only the toughest, smartest, and most feared man in football.

The Colts finished 1964 with a 12-2 mark, better than any season under Ewbank and also the NFL’s best record. Shula, in only his second year on the job, found vindication. Regardless of who opposed Shula, or why, everyone had to admit that his fiery leadership and ability to repair the run game had brought the Colts back to their glory days and even restored a little luster to Unitas. The brilliant young coach and his team did it the hard way: They beat Lombardi twice and they beat Halas twice. They scored the most points in the league and gave up the fewest. Shula was named Coach of the Year, and, of course, Johnny U was exactly what his teammates thought he was, the Most Valuable Player.

The Colts were off to the championship game on the road in Cleveland; that they would win it was a foregone conclusion.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of University of Nebraska Press

Issue 249: November 2018