When Jerry Sloan passed away last week, the accolades from the NBA brethren of coaches and players who competed against him were off the charts. His career as a player with the Chicago Bulls and later as a coach, principally with the Utah Jazz, was well documented.

My first thought, which is natural in so many of these cases, was to write a column centered around where Sloan’s career started. For whatever reason — blame it on COVID-19, a stay-in-place order, whatever — I changed my mind, thinking not many would remember Jerry was drafted, not once but twice by the Baltimore Bullets. But I changed my mind again, which you’ll notice is a recurring theme in this piece.

It took Sloan two years to get to Baltimore, twice as long as he stayed, and nobody in the room had a clue there was a potential Hall of Famer in the house.

There was, however, one player who had an inside track on the notion that Sloan wouldn’t spend much time with the Baltimore Bullets. Johnny Kerr, the NBA’s resident Iron Man at the time, finished a stretch of 844 straight games in his only year with the Bullets, 1965-66, Sloan’s rookie year.

Kerr didn’t have a big impact on the Bullets’ short-lived playoff run that year, but what he learned during practice sessions influenced both his and Sloan’s career going forward.

The irony was the Bullets had moved to Baltimore from Chicago, where they were infamously known as the Zephyrs (don’t ask where that came from) only three years earlier — but now the NBA was angling to get an expansion team back to the Windy City and Kerr, a Chicago native and legendary player at the University of Illinois, was on the top of everybody’s list as the head coaching candidate.

“If I get that job,” Kerr confided, “Jerry Sloan will be the first player taken in the [expansion] draft.”

There was nothing in Sloan’s rookie year to suggest he would be a leading candidate for an expansion team. But Kerr, who knew all the others from watching them under game conditions, also knew how the 6-foot-5 Sloan beat up veteran guards Don Ohl and Kevin Loughery in practice sessions and felt he would be a perfect fit for an expansion team.

As it turned out, Kerr got the Bulls’ job, but Sloan wasn’t the first pick– because he himself had to be first before he could be named coach. Kerr and Sloan made the playoffs as an expansion team the next year and the rest, as they say, is history.

Except, well, it wasn’t quite that simple. There was a speed bump at the start and two fateful decisions along the way.

The Bullets had actually drafted Sloan the year before, 1964, after he had led Evansville College (now University) to the NCAA Small College championship, what would be considered Division II today. Sloan was the rock on that team, coached by the legendary Arad McCutchan, and was flying under the radar.

As a transfer student, Sloan was a “third-year eligible” draft prospect in 1964. The Bullets, who had drafted Gus Johnson under similar circumstances the year before, thought they caught lightning in a bottle again when they selected Sloan in the third round.

The Bullets were excited enough about agreeing to terms with Sloan that they called a press conference, only to get a phone call mere hours before that he had changed his mind. It turned out that McCutchan had convinced Sloan he would be better served by finishing his college career. It was the first of two times the coach influenced career decisions by Sloan — and the only one that stuck.

At that press conference in 1964 the only announcement the Bullets made was that Sloan was not coming — and the papers the next day carried a picture of an empty chair that had been reserved for him.

Undaunted after Sloan had led the Evansville Purple Aces to a second straight national championship, the Bullets doubled down and made Sloan their first-round pick in the 1965 draft, which teamed him up with Kerr and then the rest was history, at least as far as the playing career.

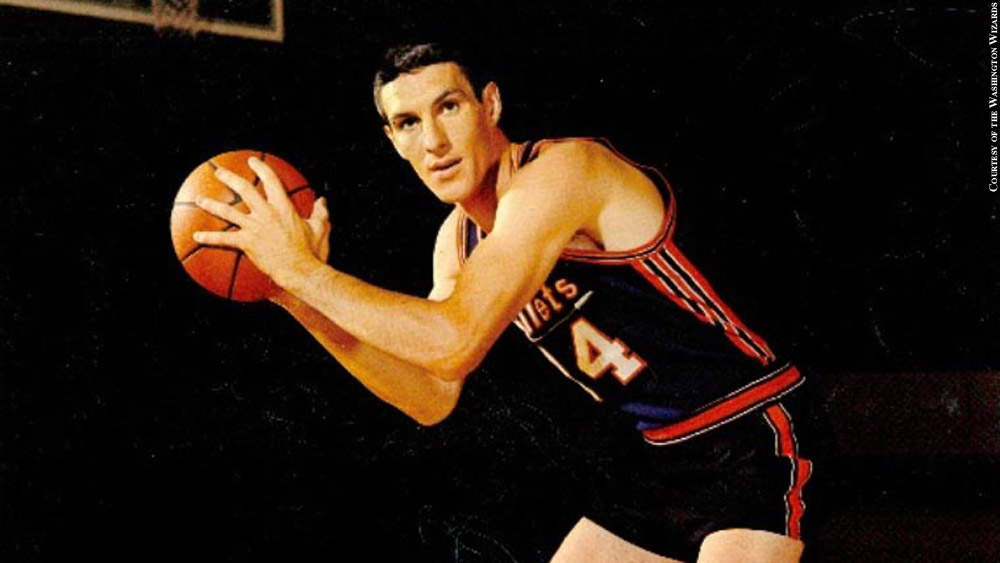

Sloan would play 11 years for the Bulls, post career averages of 14 points and 7.5 rebounds a game — not bad for a defensive-oriented guard with elbows as sharp as knives and knees ravaged by floor burns. He became known as the “Original Bull” and his number, 4, was the first retired by the Bulls.

And then fate took over.

Sloan’s knees finally wore out and he retired 1976, the year before his very influential and beloved college coach, McCutchan, decided it was also his time to step aside. A native of Evansville, where he is still revered, Sloan was a natural to succeed his coach, who in turn highly recommended his protege as his successor.

Again, Sloan accepted an offer. And again, he changed his mind. Heeding advice from NBA insiders who convinced him he had a coaching future in the league, he turned down the job five days later.

And then, for the third time, the rest is history.

Sloan would coach the Bulls for three years, winning the only division title before Michael Jordan came along then getting fired the next year. Getting fired was the easiest part of that chapter in his life.

On Dec. 13, 1977, the first year of the post-McCutchan era, what would have been Sloan’s first year as a college coach, a plane carrying the Evansville basketball team crashed on takeoff. There were no survivors.

It was a traumatic time for Sloan, who didn’t talk much about how fate impacted his life, but neither did he let it dull the determination that was the trademark of what can only be called a remarkable career. His next stop was Utah, where he led the Jazz to an unprecedented 16 straight playoff appearances, losing their only two playoff finals to the Bulls in 1997 and 1998, the last two titles of the Jordan era.

Sloan retired with a career coaching record of 1221-803. He is one of only four NBA coaches to go at least 15 straight years without a losing record. He was elected to the Naismith Basketball Hall Of Fame in 2009.

He never won a “Coach of the Year” award. Believe it or not, somehow that is also history.

Jim Hennemn can be reached at JimH@pressboxonline.com

Photo Credit: Melissa Majchrzak/NBAE via Getty Images