Looking back on the 2001-02 Maryland men’s basketball team’s national championship, it is rather easy to conflate the terms “culmination” and “celebration.” To take nothing away from the specific players on the 2001-02 squad and their unique accomplishments, that championship always felt like the consummation of an entire period that began with Gary Williams’ return to his alma mater in 1989.

Winning the national championship felt like a bit of a formality that night in Atlanta. The Terrapins were in their ninth straight NCAA Tournament, a run that had included six Sweet 16 berths and consecutive Final Four appearances. They were supposed to win the title by that point.

But just 10 years before that, the program was banned from postseason play and a year removed from a season-long television ban.

So how exactly did Maryland climb from the depths of NCAA sanctions to finally fulfilling the destiny Lefty Driesell had once imagined for the program? PressBox’s Stan “The Fan” Charles and Glenn Clark spoke with Williams for a revealing conversation about that very question and how his perspective of the championship has changed 20 years later.

This interview has been edited for content and clarity.

PressBox: When you took the job to come to Maryland, how hard of a decision was it to leave Ohio State? Was that a hard decision for you?

Gary Williams: Yes, it was. I wouldn’t have left Ohio State for any other job, having gone to Maryland, played some basketball there, that type of thing. Wherever you go to school, that’s never going to change. You can change a lot of things in your life, not where you went to school. So that was always with me. Even when I played in the ACC back in the mid-’60s, I always felt that we never marketed the program, really went after it like a Duke or Carolina or places like that, so that was always in the back of my mind, I guess. That was one of the reasons I could take the job at Maryland because [Ohio State] had just signed Jimmy Jackson. We had been good there. We were going to be good. We had some really good players coming back. The second year I was gone, they missed a jump shot to go to the Final Four against the Fab Five from Michigan. They were going to be good, so I would’ve never left except for the Maryland job.

PB: If we go back to 1989 when you decided to come back, clearly you were saying all the right things. But in hindsight, in 1989 were you confident that you were ultimately going to be able to win a national championship at Maryland?

GW: In ’89 when I came back, I wasn’t aware of the severity of what the sanctions would be from the NCAA. We found out the week of the ACC tournament that first year, so that’s the spring of ’90. Typical NCAA, they did it the week of the ACC tournament when we had a pretty good team. We won 19 games. We had Walt Williams, [Jerrod] Mustaf, [Tony] Massenburg, good players. And we could’ve done something, I think, in the NCAA [Tournament]. We beat Carolina twice that year. We beat Southern Cal. George Raveling was the coach. They had Robert Pack and Harold Miner as their guards, so it was a really good team. We had some things, but we didn’t even get a look because the NCAA didn’t want us in the tournament that year, that was for sure, because they were going to hit us with sanctions that nobody else had gotten that severe. You look at schools now, they get sanctions, they get three years probation. Know what that means? Nothing. We got two years no NCAA, [one year] no live TV, three scholarships reduced and a fine. Maryland did not do a good job of fighting the NCAA. We did not hire outside counsel like most schools do when they get investigated by the NCAA. So there were a lot of things there that you kind of got hit in the face [with] that you didn’t expect when you came. [Everyone has] taken different jobs. You think you know the job coming in, but until you really get there and start to work, then you really find out about the job.

PB: When you came out of the sanctions and you had started to right the ship in the early- to mid-’90s, did you rebuild belief at that point?

GW: I think that’s a good way to put it. The year before Joe Smith and Keith Booth came, we started three freshmen — Johnny Rhodes, Exree Hipp and Duane Simpkins — and they got valuable experience so that when Joe and Keith did come on board, we got good in a hurry. I think we won three [conference] games total — two regular season, one ACC tournament — the year before Keith Booth and Joe were freshmen, and then we got to the Sweet 16 [the following] year. It went quick. … People have short memories in sports, like a lot of things, but in sports there are short memories. But they were willing to put the past behind them, and that’s what I was concerned about. There was a feeling on campus when I got here in ’89 that basketball had been bad for the university. There had been things that had happened, with [Len] Bias, with Bob Wade coming in, that didn’t put the university in a good light, and I think there were a lot of people just on campus and obviously some others that felt basketball was not good for the university. There was that feeling that you had to overcome. So that was one of the biggest things that that first team with Joe Smith and Keith Booth did was overcome that feeling of a lot of people.

PB: During the era coming out of the sanctions, did you talk about a national championship, or was it just about building a program? Was the concept of winning a national championship significant?

GW: Around ’93, ’94, it was still about building a program because we had just gotten good [enough] where we could make the NCAA Tournament, things like that. It was important to really do it the right way, to build it where it was solid, where we could continue to be a threat to make the NCAA Tournament every year. I think that was our first thing we looked at. From there, after we started going to Sweet 16s, it became more of, “We’ve got to get past the Sweet 16. We have to be able to do that,” and that’s when we started thinking about winning a national championship. The problem was that Maryland had never been to a Final Four, so you had this kind of glass ceiling there that you had to break through. And it’s hard to do. You see it with a lot of schools. They’re good — really good — but they just, for whatever reason, they don’t win a national championship or they don’t get to the Final Four.

PB: Was the high level of competition in the ACC a good thing when building the program?

GW: The good thing was you had two teams in there — Duke and Carolina — that every year, they were picked top five in the country, basically. So you had a good look at what you had to do to be successful. In other words, if you looked at those two programs, they had continuity with their coaches, the schools really emphasized basketball … so you had a lot of things you could point to, but it was up to the university if they wanted to go in that direction and make us what we could be in basketball. The difference was we’re in a professional area. I think there are seven major professional franchises within 35 miles of College Park, and that changes things. People only have a certain amount of money for their entertainment dollar. For football, for example, if you go to a Ravens game on Sunday, you might not go to the Maryland game on Saturday because you can’t afford it to take your wife, a couple kids, things like that. This is a unique job. The University of Maryland job is a unique job, and I think you have to understand the job coming in to really be successful.

PB: What was the single biggest hurdle that the entire program or the entire athletic department had to overcome in order to move into the echelon of being a program that was capable of winning a national championship?

GW: I think after what had happened right before I got the job, we had to prove that we were going to do it the right way. There were a lot of skeptics on campus. “OK, here comes another basketball coach, what’s he going to do now?” — that type of attitude. You had to dispel that. I did a lot of things — speaking on campus, speaking with faculty groups, speaking with student groups, going to Baltimore to try to mend some fences in Baltimore. All those things had to be done if we were going to be successful. That didn’t bother me to have to do that because I wanted to be successful, but at the same time, it took a lot of effort from not just myself but our staff. You really had to make sure people understood what we were going to try to do with the program — make it a good program, as good as anybody in the country, but at the same time, do it the right way, not try to take shortcuts, not try to do anything that’s going to hurt the school because I think there was that fear factor when I got the job that, “We don’t want anything else to happen with basketball,” so you had to be careful going in there.

PB: In looking back on the championship itself, do you find yourself reflecting on the players who weren’t on that team but who were just as important because they helped get the program to a point where it could win it all?

GW: Oh, sure. It’s not a magic thing. Those players who played on the 2001 Final Four and 2002 championship teams, they all saw guys like Keith Booth, Joe Smith, Johnny Rhodes, Steve Francis, Rodney Elliott. It’s one thing for a coach, you’ve got a spiel when you recruit. “We’re going to do this, we’re going to do that,” whatever. But at the same time, they look and they see for themselves. Well, how did those guys do at Maryland? They liked the way they played, they thought they got better when they were here, and they were all key things for us to recruit the guys that played on the championship team.

PB: You had an upperclassmen-laden team, but they weren’t necessarily highly-regarded recruits. When you got a Juan Dixon, Lonny Baxter, Steve Blake or a Drew Nicholas, did you have any clue then that that was the nucleus of what was going to be your breakthrough championship team?

GW: I thought they were all good players. A lot of times when you recruit, it’s easy to see the negatives in a player and not see all the positives, and I always tried to be positive. I saw in Juan Dixon, for example, a guy that would do anything to win a game. He was incredible in how hard he played at Calvert Hall, all the time just working really hard. A guy like Lonny Baxter, he was overweight, but he had great hands. If he got the ball in certain areas around the basket, he was going to score, you couldn’t stop him. I don’t care if you were 7 feet, you couldn’t stop him. Chris Wilcox in Raleigh, North Carolina, didn’t play hard, but I saw him play the night before we played NC State down there in a high school game and he made a couple blocks that you can’t teach. They were just innate in a player’s timing and things like that, and so you look for that. And a guy like Byron Mouton transferred in, but he had averaged over 20 points a game at Tulane, but they didn’t win. They had very poor seasons, and all Byron wanted to do was win. So I think the key thing with [each player], they might not have been the most heralded players in the country, but nobody wanted to win more than those guys. They all had a reason why they wanted to win, and I thought that was the key to us winning the championship.

PB: The Valentine’s Day game against Florida State during the 2000-01 season was an ugly scene. Did you know then what your team was capable of? Or were you concerned after that night against Florida State?

GW: I was disgusted. I was disgusted that I couldn’t get the team to play better because I thought we were good. We were a year away, realistically. We were young that year. But after that game, it’s kind of like you draw the line. You either keep fading away or you snap out of it and get better. We went through about a nine-day period where we couldn’t win. We were playing OK. That’s what I remember. We weren’t playing great. We weren’t shooting the ball great, but we were playing OK. But then we finally won a game and all of a sudden we got it back, and that’s what’s weird about basketball. It’s just like shooters. They can miss their first four shots, all of a sudden they make their next six taking the same shots. How does that happen? Well, we stayed together. That’s how it happened. And that’s when I knew, after we got to the Final Four that year, that we had a shot the next year to win the national championship because we had really stayed together and we knew what it took to get there. Once we got to a Final Four, then those guys believed they could win a championship.

PB: When you broke through and made it to the Final Four, was that the first time that you legitimately knew, “OK, this program can win a national championship, these players can win a national championship?”

GW: Yeah, because it always felt at Maryland you’re on the outside looking in. You go to the basketball conventions, which are around the Final Four every year, you see those teams and you say, “Well, we played against those teams. We beat one of those teams. We beat two of those teams. How come we’re not in the Final Four?” And that was hard. That was hard to get to that next step. But I think 2001 gave us the opportunity to have a team good enough to get there and then we took advantage of that by getting there. It was a rocky road in 2001, there’s no doubt about it, with the loss to Florida State, what happened a couple games after that. That was a very satisfying year, looking back now thinking about it, to come back from that. You look at seasons a certain way and you can always look at the number of wins, how far you went in the NCAA [Tournament], whatever, but to come back from where we were and where the fans felt we were — we really got booed off the court against Florida State, there’s no doubt. Some guy was screaming at me walking through the tunnel there at Cole about, “Good luck in the NIT.” I was old enough where I couldn’t jump high enough to get after the guy, so thankfully Cole was built that way. It was a tough time to go through, but it’s the old story. Teams go one way or the other. You either get better from that or you quit. We would never quit. Those guys would never quit.

PB: In 2001-02, your team was fifth in the country in offense at 85 points per game and 176th in defense at 70.9 points per game, but would you agree that your championship run was fueled by defense?

GW: We held teams under 40 percent [from the field] that year for the season. That’s a stat I always looked at. If you run — we scored 85 points a game, fifth in the country in scoring — the other team’s going to get the ball a lot more times than if you walk the ball up and take 25 seconds off the shot clock before you shoot. So we were going to go. I had good players, so the thing with good players is you let ’em go. You trust their judgment, they’re going to take good shots, all those things. But the key stat for me is field-goal percentage, and we held teams under 40 percent for the year, including all the NCAA Tournament games, which is really hard to do.

PB: Do you have any moments from the 2002 NCAA Tournament run that really resonate with you? Were there any moments that were particularly memorable to you?

GW: The fact that we beat Kentucky, Connecticut, Kansas and Indiana really meant a lot to me because they’re blue bloods. They’ve all won multiple championships. We had never won a championship. I remember that very well. The other thing is the Connecticut game was the best game in the tournament. There were [seven] NBA players eventually on the court. … I mean, Caron Butler had 26 against us in the second half, and we had Byron Mouton on him. [Mouton was] a great defensive player. We gave Mouton a scouting report the day before when you’re practicing and getting ready. We told him, “Whatever you do, make him shoot from outside. He can’t make jump shots. He’s really tough if he gets to the basket.” He made every jump shot he took in the second half. Byron’s really got a good personality. I remember Butler making one and Mouton just looking at the bench going, “What are you telling me?” It was that type of thing.

But I remember specifically Juan Dixon hitting the three to tie it up [at 77 with less than four minutes to go]. Connecticut was up three, Juan made the three, but if we would’ve missed that, Connecticut would’ve gone down and probably scored because Butler was so hot, and that would’ve put them up five. It would’ve been difficult to come back then. But what happened was we made the shot. That put the pressure on Connecticut to score. They missed … and Steve Blake hit a three [to put Maryland up, 86-80, with less than 30 seconds to go], which, by the way, was his only field goal of the game. Then we made free throws, which we were a very good free-throw shooting team under pressure that year. We missed some when they didn’t really matter, but under pressure we didn’t miss many. And that got us to the Final Four.

Then in the Final Four, the thing I remember most, we played Kansas. They had been No. 1 in the country a lot of the time. Drew Gooden and some really good players were on that team. We come out, we get down [13-2]. We call timeout and I’m ready to go off just because we were tight. There was no doubt about it. We were tight probably because of what happened the year before, blowing that lead to Duke. We get out there and do that, we call timeout, I’m ready to go crazy, and Juan Dixon coming off the court has Wilcox — Wilcox by now is about 250 pounds. He’s kind of dragging him off the court, just killing him, just telling him how easy he was to score on, why he couldn’t get a rebound and everything like that. But the thing about Juan Dixon, after that timeout was over he went back and he hit two straight threes, and all of a sudden it’s [17-13] and it’s anybody’s game. And then we probably played the best 20 minutes … we played all year. [Maryland had a 70-55 lead midway through the second half]. I remember that very well.

PB: When you think back on your coaching career and the run to win a championship, what do you reflect on in particular when you think back to that time period?

GW: A lot of things, [including] how fortunate you are to do it, because we’ve all seen teams that are really good that just something happens — sprained ankle, bad shooting night, the other team gets hot. I had a couple teams I thought were good enough to be in the Final Four that didn’t get there. You don’t understand it all the time. I feel fortunate about that.

My high school coach is a great man. He’s still alive. He’s 90 years old. John Smith is his name. We had a big thing where I grew up in South Jersey. There was a tradition that you wore your school clothes — and back then, people actually dressed up to go to school — as soon as class was dismissed the last day and you played pickup basketball for about four hours. That was the big thing. And I remember feeling this guy grab the back of my neck. This is after my junior year. I had gotten a D in Latin and a D in Geometry. And by the way, if I took them today, I might fail them. I still remember that. I get nightmares about those two courses. They were horrible. But anyway, he made me march back into high school. I had to register for summer school and I barely got C’s, but the grades got good enough where I could go to college. I’ll never forget that. He was more than a coach to me.

And then Dave Gavitt, the commissioner of the Big East, I got to know when I was coaching at Boston College and then stayed good friends with Dave. He was like a guru. He was a guy you could talk to. He was probably as big as there was in college basketball, but he was a regular guy. He had coached at Providence — Marvin Barnes, Ernie DiGregorio, great players in the past. Dave was a good friend. He just kept me going in the right direction. Whenever things got tough, you could call him. He’d give you his side of the story and calm you down or whatever he had to do. Those people were great in your life, but the players are what keep you going in coaching.

Like the last part of my coaching [career], I had Greivis Vasquez. It was just unbelievable to coach a guy like Greivis Vasquez. He’d walk into practice every day, he was so happy to be at practice. He was incredible, and that’s what you need. That’s all part of being a good team is to have people that want to be there, that love the game, that want to get better and that put up with you, because it’s not perfect. You’re not perfect as a coach. You yell at guys when you shouldn’t yell at guys. You may say something that they really don’t like, but really mature people come in and you talk it out the next day and you’re ready to go the next day in practice, so I really appreciated the players.

PB: Has the way that you reflect changed at all in 20 years? Do you feel differently about the championship run than you did 20 years ago?

GW: I appreciate it more, probably, because you watch a lot of games. I probably watch more games now because you’re not getting ready to play yourself, so you’re able to see Pac-12 games or whatever. You see a lot of really good teams, like I said before, that just don’t get there for whatever reason. I appreciate what the players did because they were good. Four of the five starters play in the NBA and the fifth, Byron Mouton, if he would’ve gotten to the right team, he probably would’ve made it somewhere. I appreciate the fact that they were able to stay very focused, confident, borderline cocky, but yet when it came time to play the game were willing to sacrifice scoring. Steve Blake averaged [8.0] points a game the championship year and played 13 years in the NBA, for example. I think we had the most assists of any team going into the NCAA Tournament in 2002. We were very unselfish, and we had guys who were willing to play defense. You hold your opponents under 40 percent for the season, you’re playing defense on a consistent basis. I think that’s what we were willing to do, and our players were mature enough to know that. Regardless of how good we were offensively — we were good, going 85 [points] a game — we still had to show that we were willing to play on the defensive end of the court.

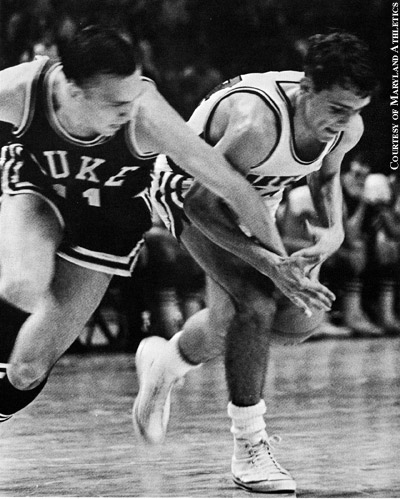

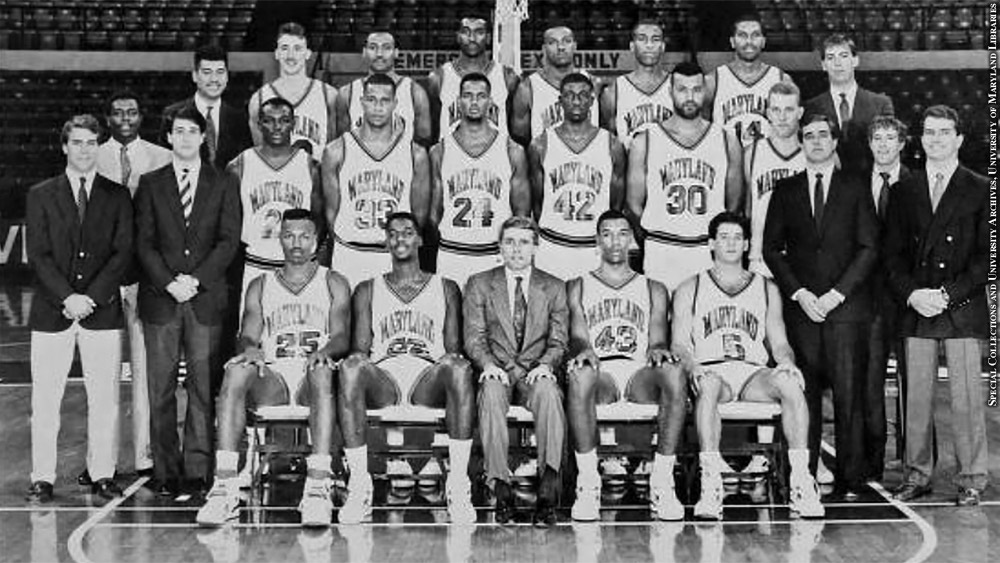

Photo Credits: Kenya Allen/PressBox, Courtesy of Maryland Athletics, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Maryland Libraries