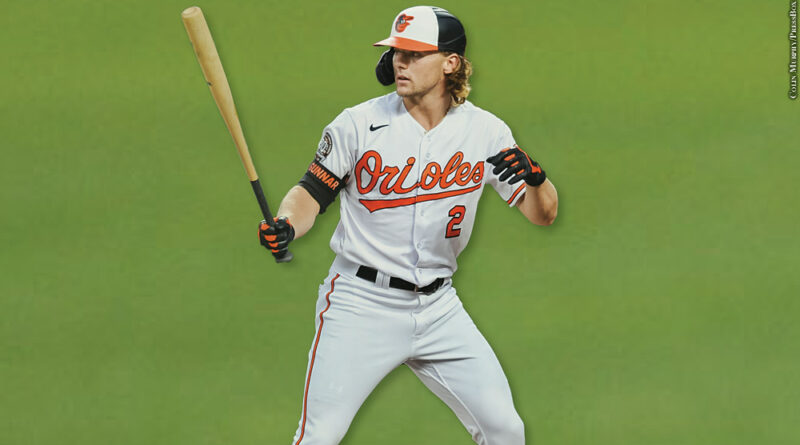

Summer had descended upon Aberdeen in 2021, and Gunnar Henderson was struggling.

Henderson was mired in a 1-for-31 start for High-A Aberdeen that began on June 22 and extended through July 3, with his 20th birthday falling on June 29. The Orioles’ 2019 second-round pick had begun the season at Low-A Delmarva, hitting .312/.369/.574 in 35 games for the Shorebirds before getting the bump up to Harford County, but now, for the first time in his baseball life, no hits were falling in.

“That was the first one of that magnitude of a stretch,” Henderson said. “That was my first big one, I guess.”

Henderson snapped the skid with a 3-for-4 night on July 6 that included a double and a home run. The left-handed hitter finished his 65-game stint with the IronBirds hitting .230/.343/.432 with 28 extra-base hits, a more-than-respectable showing given his start, age and Aberdeen’s pitcher-friendly environment.

But it was his struggles with the IronBirds that proved instructive to Henderson’s offseason following the 2021 campaign, as the infielder headed home to Selma, Ala., with lessons from the slump that ranged from swing mechanics to his mindset.

Henderson followed up that offseason with a 2022 campaign that saw the 6-foot-2, 220-plus-pound infielder rip through Double-A Bowie and Triple-A Norfolk and finish in Baltimore at the age of 21 as one of the linchpins for the club.

Henderson’s rise is fueled by a work ethic and competitive fire instilled in him by his family, a love for the game of baseball that began in his back yard and a skill set that has a chance to make him a staple in Baltimore for years to come.

“I feel like the work ethic that my parents have instilled in me and having the competitiveness of growing up with my brothers,” Henderson said when asked how he was able to make such a big leap in such a short period of time. “I felt like that’s just something that is going to help me in the long run and help me to continue to get better and better each and every offseason and every year.”

BACKYARD BEGINNINGS

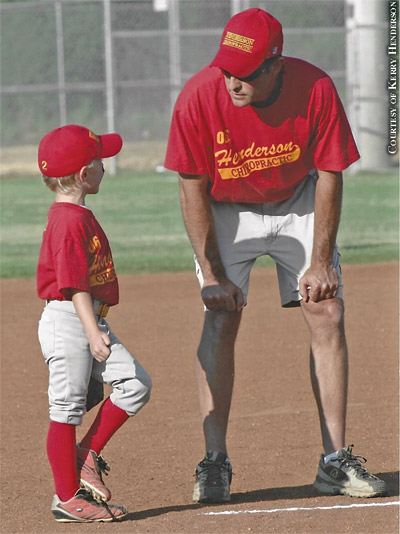

Gunnar Henderson’s journey to Baltimore started in the back yard of the Selma home his family moved into when he was 3 years old. Henderson’s older brother, Jackson, was already playing city league baseball, but it was a frustrating process for the team to practice because there weren’t many practice fields around town.

Turns out, the family had a back yard big enough for Gunnar and Jackson’s father, Allen, to build a ball field complete with outfield fences that stretched out to about 250 feet in center.

“You couldn’t always have access to fields to practice on, so it just made sense that we turned what used to be a small horse pasture into a little league field,” Allen said.

That gave Jackson’s team a spot to practice. It also gave Gunnar and his cousin Brayton Brown, now an outfielder for UAB, a chance to follow in Jackson’s footsteps. Gunnar and Jackson’s mother, Kerry, remembers Gunnar and Brayton turning double plays by the time they were 4 years old.

Brayton recalled how the setup ignited his and Gunnar’s competitive fire.

“It always ended up me and Gunnar, four or five years younger than Jackson, versus Jackson and his friends. So it got super competitive,” Brayton said. “When we were younger, we were always getting our butt whooped because they were so much older than us, but I think that just instilled the competitive drive that we’re going to beat these guys one day.”

Whatever sport was in season was Gunnar’s favorite as he was growing up, but he tended to gravitate toward baseball. When Gunnar was 7 years old, Allen began a travel ball team called the RockHounds that practiced in the Henderson back yard. The squad included Gunnar, Brayton and any other kids around town that wanted to give baseball a try.

Not long after, Gunnar joined the Cracker Jacks based out of Prattville, Ala., about an hour away from Selma. Mitch Parker, his coach with the Cracker Jacks, remembers a big kid who carried an uncommon competitive drive and edge.

“The first time I saw him at one my practices, I did not know Allen at all and I introduced myself to him,” Parker said. “I shook his hand and I told him I expected to see his son play on TV one day.”

Soon enough, more observers began to share that opinion.

“I remember probably he was about 11 or 12 on a travel ball team and [I was] having a conversation with one of the dads, talking about the team and different players,” Kerry said. “He said, ‘And then you have a freak like Gunnar.’ I just looked at him and he had a smile and I’m thinking, ‘He just called my child a freak. Is that a compliment?'”

SELMA STAR

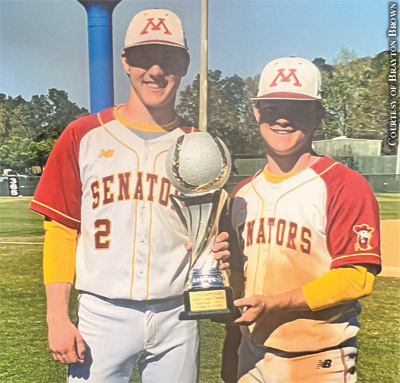

Gunnar Henderson and cousin Brayton Brown attended Morgan Academy, a K-12 school in Selma, together from first grade on. By the time both were in eighth grade, they were so advanced as baseball players that they were asked to play for the varsity squad during its playoff run. Henderson played high school football, basketball and baseball through his 10th-grade year, then left his days as a quarterback behind to focus on the latter two sports during his final two years.

As a senior during the 2018-19 school year, Henderson won the Alabama Independent School Association’s Player of the Year honors in hoops by averaging 17 points and 11 rebounds and then was named Alabama’s Mr. Baseball by hitting .559/.641/1.225 with 37 extra-base hits.

Henderson believes he could have played college hoops if he put the necessary effort in, but baseball was always going to be his ticket. During his high school years, Henderson played travel ball in the summer and fall — eight to ten games per weekend in the summer and six to eight games per weekend in the fall — for The Prospect Lab, based in Birmingham, Ala.

Travis Coleman, his coach for TPL, was impressed by Henderson’s reliability and enthusiasm.

“The one thing we always tell the guys is that the best ability is availability, no matter what your talent level is,” Coleman said. “And Gunnar was always available. I never honestly remember Gunnar missing a tournament or a game that he could be at. He always posted no matter what the level of competition was or where it was or who it was. He posted with the same attitude. You never had to get him going.”

Henderson began getting scholarship offers for baseball as a sophomore at Morgan Academy, and by his senior season, there were occasionally 30 to 40 scouts from major league clubs at his games. Henderson’s expectations for himself were so high that he became frustrated after a stretch in which he didn’t get a hit for … four or five at-bats.

Morgan Academy baseball coach Stephen Clements could tell his star shortstop was pressing and tried to put him at ease.

“He and I were kind of sitting down having a conversation,” Clements remembered, “and he was like, ‘Coach, I just feel like every ball that I hit, I’m supposed to hit it over the wall and over the scoreboard and all these guys are watching me.’

“I said, ‘You know, Gunnar, all these scouts, when they call me,’ and I talked to 20 a day sometimes, ‘they don’t ask me your stats. They don’t ask me that all the time. They want to know what Gunnar’s like when it’s hard times and when you struggle. You don’t have to have all that pressure. Just relax and go play baseball.'”

Henderson verbally committed to attend Auburn University in 2017, then signed his national letter of intent to become a Tiger in 2018. Cousin Brayton Brown had also signed to go to Auburn, and brother Jackson had one year left with the program, so the idea was to all play together at Auburn.

Henderson expected to go in the first round of the 2019 MLB Draft, but he ended up being taken with the first pick of the second round, No. 42 overall, by the Orioles. He had met eventual signing scout David Jennings at a tournament in 10th grade, but he didn’t have any contact with the Orioles leading up to the draft. Regardless, Henderson signed for an over-slot bonus of $2.3 million.

Henderson credited Jackson for putting him at ease ahead of the final decision. Jackson told his younger brother to follow his heart.

“After seeing people go through the SEC and turn down money and then end up coming out making less on the back end, it’s just such a risk to run, and the years of wear and tear on your body,” Jackson said. “Obviously, selfishly, it would have been cool to be able to play together, but I think that opportunity that he was given with a great organization, you have to look at it and just see how big of a blessing it was for all the stars to align on that.”

“THIS IS INTERESTING”

After signing with the Orioles in 2019, Henderson reported to Sarasota, Fla., to get his feet wet in pro ball. He hit .259/.331/.370 with eight extra-base hits in 29 games in the Florida Complex League. The following spring training was cut short by the exploding COVID-19 pandemic, and the minor league season was eventually canceled.

However, major league teams played a 60-game schedule beginning in late July and had “alternate sites” to keep players ready for a call-up and develop select prospects. Henderson, one of the prospects chosen by the Orioles to report to the Bowie alternate site, called it “probably one of my favorite experiences so far in pro ball.”

Henderson said he’d come to the ballpark at 10 or 11 a.m., stretch, take some ground balls and hit in the cage before digging in to face pitchers in game-like at-bats. He estimates he’d take between seven and nine at-bats per day against big-league-quality arms. His first at-bat came against minor league veteran Eric Hanhold.

“He was 97-99 and then I remember getting down 0-2 in the first at-bat and then he drops a 92 mph changeup. I swung at that and I was like, ‘Well, this is interesting,'” Henderson said. “That was pretty much my wakeup call. It was my first at-bat. After kind of settling down after about a week or two, I felt like I really held my own and had some really good ABs.”

Ryan Fuller, now the Orioles’ co-hitting coach at the major league level, worked with Henderson at the alternate site to create a larger margin for error with his swing by “getting on plane deep in the zone and being able to stay through the front of the zone, too.” Making those adjustments, as well as facing high-level arms at the age of 19, jumpstarted his development, according to Fuller.

“If we had a normal year, he would’ve gone to Delmarva, maybe made a run at High-A, but certainly not be able to see that Triple-A, big-league-level stuff,” Fuller said. “It was so much fun to be around him every day to experience it, get knocked down a little bit, have some success and then be able to see, ‘Man, the work I’m putting in is really helping.'”

QUICK RISE

Henderson began the 2021 season at Low-A Delmarva before making the jump to High-A Aberdeen, where he bounced back from that 1-for-31 start. He got bumped up to Bowie for a taste of Double-A ball at the end of the season before heading back home to Selma. That offseason, he worked in the batting cage he built in his parents’ back yard with specific goals in mind.

Henderson wanted to flatten out his swing some because he had too much swing and miss in his game, particularly at the top of the zone. High-A pitchers had busted him inside to counter his trademark opposite-field power, so Henderson went from a closed stance to a neutral one. He also developed a renewed understanding that there was no reason to panic if hits weren’t falling in.

During spring training, Henderson worked in the cage with baseballs that exaggerate hop at the top of the zone.

“I hammered that, really hammered that out during spring training,” Henderson said. “I felt like that really helped my swing and was able to get to those ones at the top of the zone and then whenever they missed down in the zone, just drop the barrel head on it. I felt like that was a really big step in my development.”

Henderson exploded in 2022, hitting .297/.416/.531 with 50 extra-base hits between Bowie and Triple-A Norfolk before making his major league debut in Cleveland on Aug. 31. His minor league strikeout rate dropped from 30.9 percent in 2021 to 23.1 percent in 2022. His walk rate rose from 12.9 percent to 15.7 percent.

Henderson credited the work ethic and competitiveness he acquired at an early age for his rapid improvement as well as the values his parents instilled in him, older brother Jackson and younger brother Cade, including humility and levelheadedness.

“You can always run into somebody who’s better,” his father, Allen, said. “I know some seem to think it’s appropriate to have necessary arrogance to be successful. I don’t personally agree with that. But it’s just something that me and my wife have taught the kids — just don’t be arrogant no matter how successful you are.”

WORLD SERIES DREAMS

Henderson hit a home run in his major league debut en route to batting .259/.348/.440 with 12 extra-base hits in 132 plate appearances during his first taste of the big leagues. He retained his rookie eligibility, and Henderson opened spring training in 2023 as the consensus No. 1 prospect in baseball.

Provided he remains healthy, Henderson will play nearly every day for the Orioles in 2023, with his 22nd birthday coming in late June. He played 24 games at third base, seven at shortstop and three at second base down the stretch in 2022.

Henderson credits Orioles infield coordinator Tim DeJohn for cleaning up his footwork and throwing motion in the minor leagues, where he played mostly third base and shortstop. During his stint at Bowie in 2022, Henderson shared shortstop duties with fellow prospects Joey Ortiz and Jordan Westburg.

Ortiz said he never felt as if the three were competing for shortstop, pointing to DeJohn for instilling the right mindset in them.

“He was always just telling us we’ve got to be ready to play everywhere because that’s where the big league team might need us,” Ortiz said. “As far as us being all shortstops, I know we can all play the position well. We kind of just push each other to be the best defender all over.”

In 2022, Orioles prospects who had played together at each stop of the minor league ladder graduated to the big league level. That could continue in 2023, with Ortiz and Westburg possibly joining Henderson in the majors.

Forming friendships in the minor leagues means chasing shared goals in the big leagues. That should come in handy the next time a 1-for-31 slump has to be navigated.

“It helps in every way because you have the chemistry with each and every guy and just being able to take it to the highest level and compete for a World Series is really special,” Henderson said. “I feel like going into the dog days of summer and into the playoffs, you’ve got to have that chemistry and just that bond between everybody to pull the team through those tough days. And then whenever you get on a roll, you can’t beat it.”

Photo Credits: Courtesy of Kerry Henderson, Brayton Brown, Travis Coleman and the Baltimore Orioles and Colin Murphy/PressBox